In the summer before my senior year of high school I got a series of emails from someone who was, quite literally, my secret admirer. The anonymous author had gone to great pains to conceal his or her identity, to the extent of setting up a dummy email account and keeping secret any personal details that might have given me any hints or clues as to who he actually was. The notes were, besides being flattering, very well written and polite, and we corresponded for a short while before the emails abruptly stopped. Years later, I still have no idea who the secret admirer was. And the thing that bothers me the most isn’t that I may have missed out on a chance to get to know someone who purportedly cared for me, but that I never knew who he was. It still drives me a little bit crazy that this person was, simply put, Anonymous.

Fatal curiosity is nothing new for humanity as a whole. I trust that we all know the saying about the cat by now. So many myths, legends, and folk stories tell of the dangers of excessive inquisitiveness. The fall of man in Genesis is a great example of the dangers befalling men and women who allow their curiosity to overcome them. Pandora and her box. In the Greek myth Eros and Psyche and the Norwegian tale East of the Sun and West of the Moon, young women who have married mysterious men are tempted into spying on them at night, betraying their lovers trusts and setting them upon difficult and harrowing quests. The legend of Bluebeard. The theme is repeated over and over again: secrets are better left untold, and anonymity is best preserved.

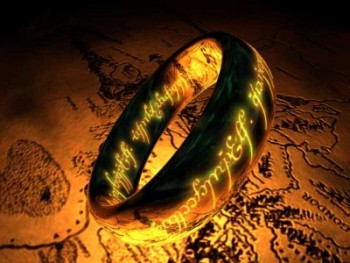

But amid all the talk of curiosity, few people discuss the role of anonymity in a complicated and difficult world. In Book 2 of Plato’s Republic, Glaucon recounts the tale of The Ring of Gyges. In the story, a shepherd finds himself in possession of a ring that grants the bearer the power of invisibility. Suddenly finding himself able to do whatsoever he pleases without fear of detection, the shepherd abandons any semblance of morality and begins to steal, seduce, and murder at will. Through this allegory, Plato seems to posit that morality is a social construction, and when these sanctions are removed human character evaporates.

While Plato’s view is somewhat extreme, I think he does have a point. I’ve been reading recently about the phenomenon of “online disinhibition,” which constitutes a loosening of social restrictions or inhibitions that would normally be present in a face-to-face interaction. While the Internet is great, it allows for varying degrees of anonymity that alter the way we interact with the people and the world around us. You can be anyone, or no one. Just look at my secret admirer: for whatever reason, he didn’t feel comfortable approaching me in real life, so he hid behind the internet. And that’s a fairly benign use of online disinhibition. Online trolls can–and do–bully and harass without fear of their identities being known. Dangerous criminals can hide behind false identities. Discrimination can run rampant without accountability.

So yes, curiosity has been identified as a leading cause of feline mortality. But trust goes both ways. Maybe these parables warning about inquisitiveness wouldn’t exist if people could be sure that everyone was presenting their best selves, with honesty and accountability.

Because nobody likes a dead cat.

Do you think there are dangers in anonymity or curiosity? Leave your thoughts in the comment section below!

0 Comments